Ontdek de collectie

Kunstmuseum Den Haag has a treasure chamber of over 160.000 pieces of art. Here we work on making the highlights from this collection available online.

Boris Lurie & Wolf Vostell

Art after Auschwitz

The confrontational art of Boris Lurie (1924 -2008) and Wolf Vostell (1932 – 1998) will be shown together for the first time in Art after Auschwitz. From the late 1950s onwards, these two artists focused on the Shoah (a Hebrew word meaning "catastrophe" used to refer to the Holocaust) in a radical way. At a time when the war was still a taboo subject in large parts of society, they chose to create art that confronted the viewer with this painful period. Combining the most appalling images of war crimes with superficial advertising images, their work is also an indictment of the post-war consumer society, which simply resumed with no regard for the trauma that the Jews and others had suffered. To create this shocking effect, both artists incorporated the most modern techniques into their work.

After meeting in New York in the early 1960s Lurie and Vostell became close friends, and they corresponded for many years. A selection of their correspondence will be shown in public for the first time in Art after Auschwitz, which will also feature dozens of paintings and objects by both artists. Vostell’s 1970 installation Thermoelektronischer Kaugummi, which was recently restored, will also be on show at Kunstmuseum Den Haag, on a once-only loan from Museum Ostwall.

Film by Studio Gerrit Schreurs

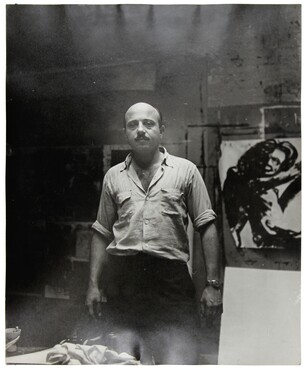

Boris Lurie

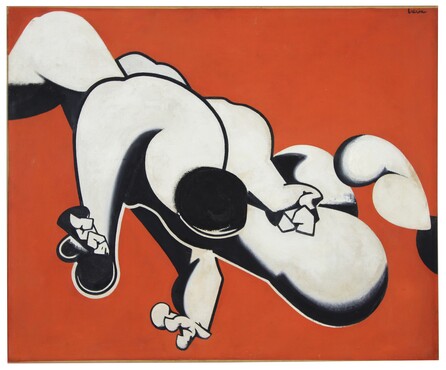

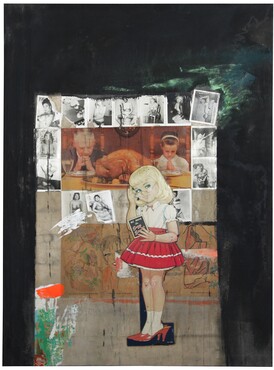

As a victim of the Shoah, for Lurie art was a way of processing his trauma. Lurie was born in Leningrad, Soviet Union, in 1924 and grew up in Riga, Latvia. At the age of sixteen his grandmother, mother, sister and childhood sweetheart were murdered by the Nazis, and he and his father were imprisoned in a succession of labour and concentration camps, including Polte Works a subcamp of Buchenwald. A year after the liberation Lurie emigrated to New York, where he began to make art, producing many paintings, collages and objects throughout his life. Initially his work was figurative – dark drawings depicting his traumatic experiences. His paintings from the Dismembered Women series express his lifelong fixation with a highly ambivalent view of women, which fluctuates between desire and revulsion, between strength and vulnerability, and between integrity and disintegration. The women in these images are always corpulent, and any natural ratio between the size of the body parts has been eradicated completely. The series refers to the loss of Lurie’s female relatives in 1941. He later began to make collages, the best known and most controversial of which is Railroad Collage (Railroad to America), made in 1963, in which a pin-up model is superimposed on a railway wagon piled high with the bodies of Holocaust victims. In the 1970s, Lurie turned his attention to the written word, and spent the rest of his life working on his novel, House of Anita, and his memoires, In Riga.

Lurie's work reflects his abhorrence of a human race that proved itself capable of murdering millions. His confrontational work accuses society of avoiding any accountability for these crimes. Showing the most hideous images of war among everyday advertising images was one of the techniques that Lurie employed to expose society’s tendency to ignore these things, to simply look the other way. He detested the art market, which was more interested in financial gain than in artistic expression. It was this view that led him, in 1959, to established the NO!art movement, together with fellow artists Sam Goodman and Stanley Fisher. At a time when visually attractive and, to his way of thinking, apolitical art like pop art was popular, NO!art’s main goal was to openly and honestly depict the reality of post-war society, including difficult subjects like oppression, violence and sex. Lurie continued to write and create art until his death in 2008. His work features in several leading collections, including those of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., MUMOK in Vienna and the Jewish Museum Berlin.

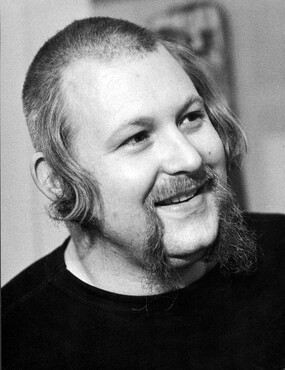

Wolf Vostell

With his parents Wolf Vostell fled from his hometown in Leverkusen and went into hiding in Czechia to flee the National Socialists. Returning to his home region after the traumatic war years the German artist’s work is a response to Germany’s post-war attitude towards the Shoah and its many victims, which sometimes took the form of blind denial. To Vostell’s way of thinking, the Germans were enjoying the benefits of an economic recovery without showing any signs of guilt, having completely suppressed all thoughts of its national socialist past. In the 1960s and 70s he confronted German society with art in public spaces that focused on the war and consumer society. In his 1969 happening Occupations (Besetzungen), for example, Vostell assumed the appearance of an Orthodox Hassidic Jew and went to parts of Berlin that had previously been home to Jewish communities. Those communities had disappeared completely as a result of the Shoah.

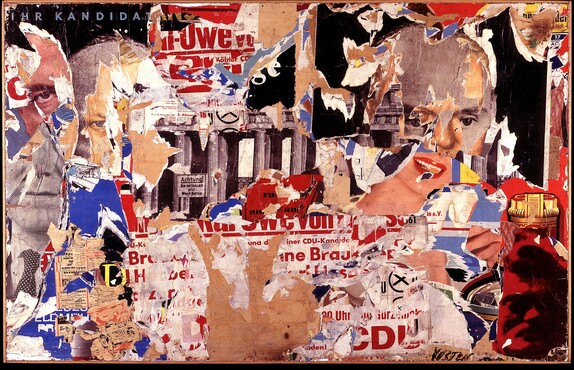

Vostell is regarded as a pioneer of installation and video art, and of sculpture in public places. In the 1950s Vostell began tearing down and deconstructing posters in Paris with the aim of exposing the superficiality of advertising. In the early 1960s he became one of the driving forces behind Fluxus, an art movement that elevated everyday objects to the status of art, in protest against the elitism of the art world. He often incorporated television sets into his work, to prompt a debate on the use of television for manipulation, though he also used the medium to disseminate his own innovative video art. Vostell became famous for his happening, which would involve spectacular actions such as publicly pouring concrete over cars, which he would also record on video. National Gallery in Berlin, Centre Pomdipou in Paris, Museum Reina Sofia in Madrid and many other major museum collections in Europe and the United States include examples of Vostell’s work.

Publication and symposium

An extensive catalogue will be published around the end of April to accompany the exhibition, featuring essays by art historians Eckhart J. Gillen, Katharina Sykora, Tom Freudenheim, Rudij Bergmann, Daniel Koep, Bram Groenteman and others. A symposium will be organised to mark the launch of the book, focusing on the impact of Lurie and Vostell’s work on the post-war art world.

The exhibition, publication and symposium are made possible thanks to the support of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation.

Caption

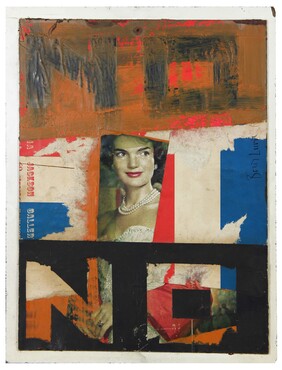

Boris Lurie, NO with Mrs. Kennedy, 1963. Acrylic and paper collage on masonite, 35,56 x 27,3 cm, Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Wolf Vostell, Ihr Kandidat, 1961. Dé-collage, 140 x 200 cm. Loan of the Federal Republic of Germany – Collection of Contemporary Art