Ontdek de collectie

Kunstmuseum Den Haag has a treasure chamber of over 160.000 pieces of art. Here we work on making the highlights from this collection available online.

Crystalline glazes

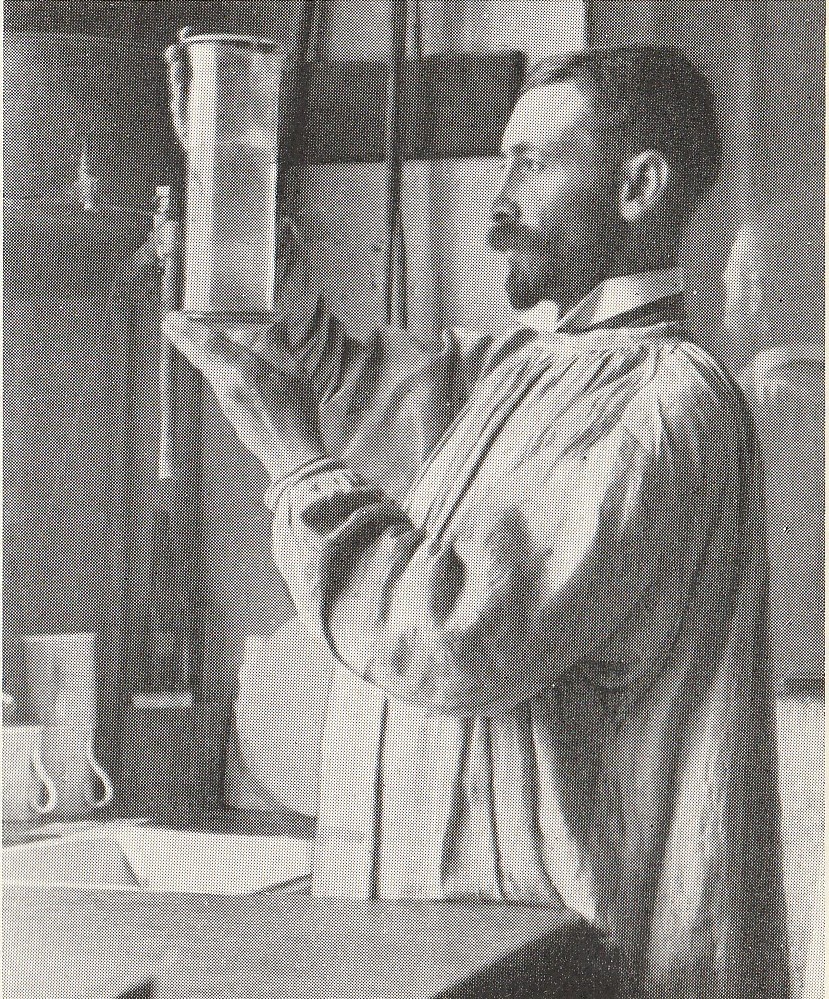

The switch to underglaze painting posed not only technical and artistic challenges but also a chemical one. At Royal Copenhagen, it was the chemical engineer, Adolphe Clement (1860-1933), who developed the colours, pastes and glazes that could withstand the high kiln temperatures. Clement was also responsible for the first experiments with crystalline glazes, which, in line with French ceramics in this period, were soon appreciated for their artistic appeal.

It was Clement’s successor, Valdemar Engelhardt (1860-1915), who really mastered the use of crystalline glazes. Apart from theircomplex composition, these glazes demand a specific firing and cooling process, in which the final crystal-like result occurs only during the solidification of the glaze at around 1100oC.The firing process, the maximum firing temperature and the temperature at which the crystals ‘grow’ are different for each glaze composition. Developing a glaze recipe and a firing schedule that gives an attractive result not only requires a great deal of theoretical knowledge, but also a great many tests.

Engelhardt scored particular success with his crystalline glazes at the Exposition Universellein Paris in 1900. However, the laborious production process and high failure rates made these pieces very expensive. This may explain why this vase remained the property of the factory until 1931. Or perhaps it was considered so successful that it was added to the ‘company collection’ as an example and source of inspiration.

In this case, the vase’s shape and the effect of the glaze seem to have been inspired more by the Chinese ceramic tradition than by Japanese art. To make the piece more contemporary, the vase was later fitted with a bronze mount by Knud Andersen (1892-1966).